Checklist of

documents in the Watts Collection at the Historical Society of Western

Virginia, Roanoke, Virginia. To consult these documents, go to http://www.vahistorymuseum.org/ and click on “Visit HMWV's Virtual Collection!” The documents can be

found by a keyword search, or by catalog number using “Click and Search”.

This group of documents dates from 1844 and early 1845, with

only two partial exceptions: document 311 involves a court case that began in

1844 and continued into the late 1840s, and 316 is a collection of receipts

dating from 1839 to 1846. Most of the documents concern the law practice of

Edward Watts and his sons James Breckinridge Watts and William Watts; and much

of that practice involved collecting debts on behalf of distant creditors,

notably in New York, Philadelphia and Richmond. One name recurs with

significant frequency: Stoner (301, 311, 321, 323, and 324); the settlement of

their affairs will be a frequent topic in the Watts papers for several years.

Some documents involve routine business matters, like the hiring of slaves to a

neighbor (309), tax payments (317), payments to court clerks (318-320). Some of

the more interesting and exceptional items include a list of subscribers to the

Richmond Whig newspaper (303); a receipt from the professor who taught music to

the Watts girls (304); a letter from the Gwathmeys, in part about tobacco and

wheat sales, but also about family news (305); a plat and survey of land at the

confluence of Glade and Tinker Creeks (307); and a letter from Henry Coalter

Cabell to William Watts, seeking his support for a candidate applying to become

professor of moral philosophy at the University of Virginia (325).

doc #

date

abstract

1998.26.301

July 10, 1844

Letter from John

Quarles James in Richmond, Virginia, to William Watts in Big Lick (Roanoke),

Virginia, whom he had recently met, requesting information about the trust deed

made by Samuel Stoner to Edward Watts, James Breckinridge Watts and Peachy

Ridgway Grattan, in particular whether the deed had been recorded by the court

clerk

1998.26.302

May 9, 1844

Receipt from Joseph

Kyle Pitzer by M. Leftwich, in Buchanan, Virginia, to Edward Watts, for 1679

pounds of tobacco, to be settled for according to contract

1998.26.303

January 17, 1844

Payment order from

Thomas W. Micou in Big Lick (Roanoke), Virginia, to Edward Watts, to deliver

payments for several subscriptions to the Weekly Whig (Richmond Whig and Advertiser) on behalf of himself, D. Lewis, James

Eddington, Landon Cabell Read and Solomon Slusher, all residents of Roanoke or

Floyd Counties, Virginia, and to deliver a letter to Kent, Kendall and Atwater,

a Richmond dry goods dealer; the payment

receipted by Newton Hill

Will

please pay the Editors of the Weekly Whig for the following subscriptions

{viz D. Lewis Big Lick Va

{ James Eddington Do [ditto]

3$ sent { Edward Watts Do [ditto]

{ Landon C. Read Stoners Store

{ Solomon Slusher Greazy Creek Floyd Co

Va

and put the Letter to Kent, Kendall &

Atwater in the Office if he can’t see them personally

oblige

yrs &c

Thos

W. Micou

Big Lick Jany 17 1844

[receipted across

the text] Received the above amount of

Five Dollars / Newton Hill / Jan 22/44

Thomas

W. Micou was postmaster in Big Lick (Roanoke), Virginia, in the 1840s. He was

married to a daughter of Elijah McClanahan and had children. He died in 1846 at

the Western Asylum in Staunton, Virginia. The

Richmond Whig and Public Advertiser; was a weekly newspaper; although the

name varied, it began publication in the 1820s and continued into the 1870s.

1998.26.304

January 30, 1844

Account statement of

Edward Watts with Gennaro F. Bozzaotra, professor of music, for instruction of

his daughters, Letitia Gamble Watts and Alice Matilda Watts in 1843 and 1844

1998.26.305

October 18, 1844

Letter from Temple

Gwathmey in Richmond, Virginia, acting for his brother Robert Gwathmey, to

Edward Watts in Big Lick (Roanoke), Virginia, enclosing an account statement

for tobacco and flour sold for Watts; statement includes names of buyers and

identifications of lots, prices and deductions for expenses, with a total of

$999.54 due for the tobacco and $449.87 for the flour; letter discusses prices

of tobacco and flour and gives advice to improve chances of sale in the future,

such as not drying the tobacco too much and using cleaner barrels; letter also

includes news of the Gwathmey family

1998.26.306

July 20, 1844

Letter from R.

Kingsland & Co in New York to William Watts in Big Lick (Roanoke), Virginia,

asking for a duplicate check to be sent, to replace one sent by James

Breckinridge Watts and apparently lost in the mail or stolen

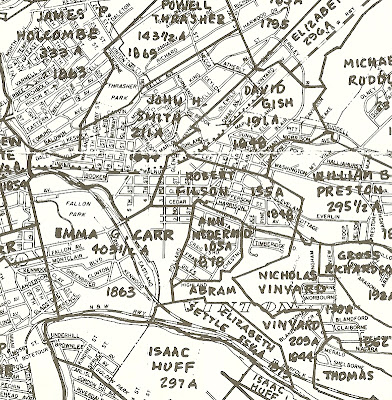

1998.26.307

December 26, 1844

Survey and plat by

Andrew Reynolds for George Ground of 271 acres of land in Roanoke County,

Virginia, lying on Tinker and Glade Creeks, which Ground sold to John H. Smith;

the survey mentions boundaries shared with property belonging to Edward Watts,

the Vinyard family, the heirs of Robert Filson, the McDermid family, and David

Gish

1998.26.308

May 20, 1844

Receipt for deposit

by James Philemon Holcombe of $1000 to the account of Edward Watts in the Bank

of Virginia, Lynchburg, Virginia, signed by W. B. Averett, teller

1998.26.309

January 17, 1844

Account statement of

Thomas Tosh with Edward Watts for hire of two slaves, Jabet and Peyton, with

itemized additions and deductions

1998.26.310

May 23, 1844

Letter from Thomas

& Charles Ellis in Richmond, Virginia, to James Breckinridge Watts, in Big

Lick, Virginia, sending a check signed by W. B. Averett of the Bank of Virginia

for $919.88, for the account of Townsend Sharpless of Philadelphia,

Pennsylvania

1998.26.311

1847 or 1848

Bill from William S.

Donnan & John Donnan, merchants, to Edward Johnston, judge of the Circuit

Superior Court of Law and Chancery for the County of Roanoke, asking for a writ

to be issued against William S. Minor, the heirs of Samuel Stoner, and John

Stoner, and many others, who were heirs of the Stoners, who held deeds of trust

for them, or who purchased property from them, or who did business with them,

for recovery of a debt; the bill includes copies of writs from 1844 and 1845,

and the defendants’ confession of the obligations, which however had not been

paid and the debtors had subsequently sold their property and declared

insolvency. The following individuals and companies are named, in addition to

the plaintiffs, judge, and primary defendants: John Bonsack; Edward C. Burks;

William Bush; Robert Campbell; Isaac Davenport, Jr.; Henry Davis, executor of

David Palmer, deceased; Robert Edmond; Alexander P. Eskridge; John Gaynor;

Gaynor, Wood & Co.; John O. L. Goggin, administrator for Stephen Goggin,

deceased; Peachy Ridgway Grattan; Edwin James; F. & J. S. James & Co.;

Fleming James; John Quarles James; James F. Johnson; Frederick Johnston; David W. Moon; Alexander K. Packer or

Parker; M. A. Painter; J. K. Pitzer, administrator of Samuel Stoner, deceased;

John H. Seay; Edward D. Steptoe; Elizabeth “Eliza” Virginia Stoner; Emiline Stoner;

Frances Stoner; John Stoner, Jr.; Kenton Ballard Stoner; Lavinia Stoner; Lenora

Ann Stoner; Louisa C. Stoner; Osborne Stoner; John W. Thompson, administrator

of William Woodson, deceased; William H. Watson; Edward Watts; James

Breckinridge Watts; William Watts; George A. Williams; Samuel Williams; Joseph Wilson;

Jackson B. Wood; Peter M. Wright, administrator for Matthew Wright, deceased

1998.26.312

December 12, 1844

Letter from Buck

& Potter, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, signed by J. Sibley, to James

Breckinridge Watts, in Big Lick (Roanoke), Virginia, asking for his services to

collect a debt of $392.74 from George W. Anderson of Christiansburg, Virginia;

they write on the recommendation of Col. W. M. Lambert

1998.26.313

November 16, 1844

Letter from Dr

Robert Johnston, in Richmond, Virginia, to William Watts, in Salem, Virginia,

asking his help in obtaining payment of $20 for assistance rendered at White

Sulphur Springs, probably in Montgomery County, Virginia, in the birth of a

child born to a slave belonging to Col Thomas Burwell, and adding a lengthy

political diatribe lamenting the results of the 1844 election, expressing

disillusionment with the idea of government by the people

I really do consider that the experiment of

free government has failed with us. We are clearly under the dominion of a mob,

who set all law, order and moral obligation at defiance, and are prepared at

any moment to trample under foot the most sacred institutions of the country,

should they appear to be in the way of any of their favourite schemes or

maxims. I believe the experiment will always fail of giving to the people,

their own government; the intelligence suffused by education is disproportional

to the actual power given them, it is not possible to equalise these two

elements.

Dr

Robert Johnston (1803-1847) is buried in Shockoe Cemetery in Richmond,

Virginia.

1998.26.314

June 21, 1844

Letter from O. A.

Strecker, in Richmond, Virginia, to James Breckinridge Watts, in Roanoke

County, Virginia, asking him to collect money from a bond of $91.88 of Dr

Thomas Goode of Hot Springs, Virginia

1998.26.315

March 2, 1844

Letter from Townsend

Sharpless & Sons, in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to James Breckinridge Watts,

in Big Lick (Roanoke), Virginia, inquiring about progress on collecting a debt

from David Fenton Kent

1998.26.316

1839-46

Wrapper and eight

brief documents relating to debts owed by or to James Breckinridge Watts or

William Watts, including receipts for payment, accounts, bonds and bad debts;

people named include Edward Watts, Christian Bowen, John Steele, J. Robertson,

Harry P. Taylor, David Gish, L. Brockenbrough, W. B. Peck, Elisabeth Bradley,

N. P. Dillard, William Nelms, and others

1998.26.317

1845

Account statement of

Edward Watts for taxes paid to the sheriff of Roanoke County, Virginia, in

1845, itemized, including 1 white and 80 black tithes, 98 slaves, 50 horses, 1

carriage, 2 gold watches, 2 pianos, silver plate and 2250 acres of land

1998.26.318

1844

Account statement of

Edward Watts for fees owed to the clerk of Montgomery County Court, Virginia,

in 1844, showing charges in a case involving Deaton and Leahy, signed by R. D.

Montague, clerk

1998.26.319

April 1844

Account statement of

Edward Watts for fees owed to the clerk of Bedford County Court, Virginia, in

April 1844 for a writ of capias against Gish, Ground and Taylor, and other

actions involved in these cases, costing a total of $5.12

1998.26.320

1845

Account statement of

Edward Watts for fees owed to the commissioner of Roanoke County, Virginia, in

1845 for a land transfer to his sons James Breckinridge Watts and William Watts

1998.26.321

January 15, 1845

Letter from Jordan

Anthony, cashier of the Bank of Virginia, in Buchanan, Virginia, to William

Watts, at Big Lick (Roanoke), Virginia, forwarding a note for $500 from Samuel

Stoner to James Philemon Holcombe, with advice about Holcombe’s intention if

the note was not paid at maturity

Jordan

Anthony (1788-after 1866) appears in the census reports of 1850 and 1860 as a

bank cashier, living in Botetourt County, Virginia. In 1860, his household

included his niece, Julia Anthony, who was married to Peachy Gilmer Breckinridge (1835-1864), a

first cousin of William Watts. James Philemon Holcombe was William Watts’s

brother-in-law. Samuel Stoner’s debts are a recurrent subject in these

documents.

1998.26.322

January 16, 1845

Letter from Henry

Homer, in Newbern, Virginia, to James Breckinridge Watts, in Big Lick

(Roanoke), Virginia, concerning a debt, unpaid because Homer has not yet

received money from a sale of bottles from Alexander and Harness, who sold the

bottles in Baltimore, Maryland

1998.26.323

January 16, 1845

Letter from Drinker

and Morris, stationers in Richmond, Virginia, to William Watts in Big Lick

(Roanoke), Virginia, asking Watts to collect debts from William S. Minor and

John Stoner, the latter resident in Bedford County, Virginia; to the former,

whose note is not due, they propose to offer reduced terms; as to the latter,

who signed an acceptance but gave a draft that was refused, they plan to file

suit

1998.26.324

January 25, 1845

Letter from John G.

McClanahan and Elijah G. McClanahan, in Lynchburg, Virginia, to William Watts,

in Big Lick (Roanoke), Virginia, explaining that they refused to pay a draft

for Samuel Stoner because he had not met his obligations, and they had notified

him to return or destroy it

1998.26.325

January 19, 1845

Letter from Henry

Coalter Cabell, in Richmond, Virginia, to William Watts, in Big Lick (Roanoke),

Virginia, asking his help in having a kinsman, James Lawrence Cabell, appointed

professor of moral philosophy at the University of Virginia, to succeed George

Tucker; he says that Benjamin Franklin Minor and other faculty are supporting

him, and hopes that Watts will use his influence to secure support from Senator

William Cabell Rives, his cousin William Ballard Preston, and his

brother-in-law James Philemon Holcombe

If you could write a letter to Mr Preston,

speaking in such terms as I hope you would feel yourself authorized to use, he

probably would have no difficulty upon your statement in giving this

recommendation. Holcombe, if with you, I am sure would join in such letter. I

hope you will use your discretion and act promptly in this matter. It is now a

subject near his heart to succeed in this application and I hope he may not be

disappointed. I write in great haste. Your friend, Henry C. Cabell

Henry

Coalter Cabell (1820-1889) had known William Watts as a student at the

University of Virginia. James Philemon Holcombe was William Watts’s

brother-in-law and a professor at the University of Virginia. William Ballard

Preston

(1805-1862) attended Hampden-Sydney College and studied law at the University

of Virginia. He served in the Virginia House of Delegates 1830-32, 1844-45, in

the state Senate 1840-44, and in the U. S. House of Representatives 1847-49.

Under President Zachary Taylor, he served as Secretary of the Navy, then

retired from political life and practiced law. He went to France in late 1850s

as a negotiator, but returned as the Civil War grew imminent. He was a member

of Virginia's secessionist convention in 1861, wrote the act which declared

Virginia's secession; he also served in the Confederate Congress. James

Lawrence Cabell was not successful in his campaign to obtain this appointment;

see 1998.26.346.