General James Breckinridge (1763-1833), my 4-great grandfather, has appeared before in this blog as the owner of Grove Hill plantation in Botetourt County, Virginia. But he also owned real estate in Washington, DC. I first discovered this fact two years ago, transcribing documents from the Watts Collection of the Historical Society of Western Virginia. Item 1998.26.202 is a letter of August 8, 1838, from one C. Smith, apparently an officer of the Farmers and Mechanics Bank of Georgetown, to Edward Watts, enclosing a statement of the account of James Breckinridge, deceased. Edward Watts (1779-1859), husband of Elizabeth Breckinridge (1794-1862) and thereby son-in-law of James Breckinridge, was one of the executors of the estate. Smith’s account statement contained a line reading:

By sale of City lots to Mr Swann $2390.31

Int on same from 1 Oct 1826 to 12 Feby 29 338.60 2728.91

and a section reading:

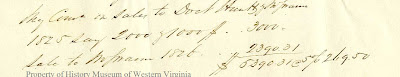

My Com[missio]n on sales to Doct Hunt & to Mr Swann

1825 say 2000 & 1000 $ 3000.

Sale to Mr Swann 1826 2390.31

$ 5390.31 @ 5% 269.50

There was enough information there, I felt sure, to track down the deeds, but it seemed to entail more effort than the results would merit. These lots were not the Breckinridge homestead, after all, probably not even a temporary residence, but more likely investment property acquired while the General was serving in the U. S. Congress, as Representative from Virginia, from 1809 to 1817. Just a few years before he arrived, the city of Washington did not even exist. Pierre Charles L’Enfant drew his plan for the city in 1791, and it was decades before even the relatively small space in L’Enfant’s map was fully urbanized. It was entirely possible that Breckinridge’s lots had no interesting history at all until well after he sold them, if then.

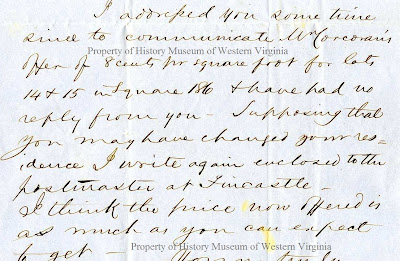

A more recent discovery led me to reconsider. Document 1998.26.467 is a letter from an unidentified man named Walter S. Leon. He wrote to General Breckinridge’s son Cary (1796-1867), a co-executor of the estate, on November 29, 1850, as follows:

I addressed you some time since to communicate Mr Corcoran’s offer of 8 cents pr square foot for lots 14 & 15 in square 186 & have had no reply from you. Supposing that you may have changed your residence I write again enclosed to the postmaster at Fincastle. I think the price now offered is as much as you can expect to get.

Square 186 designates the block at the corner of Connecticut Avenue and H Street. It is on the north side of Lafayette Square, which was originally intended to be part of the White House grounds. In the early nineteenth century, it was one of the most elegant neighborhoods in Washington. The first house on the square was built for Commodore Stephen Decatur in 1818; it is also the last one still standing, and now houses a museum devoted to White House history.

Decatur House

Furthermore, the name Corcoran is immortalized in Washington by the art gallery that William Wilson Corcoran (1798-1888) endowed and filled with his art collection, one of the first public art museums in the nation. Corcoran was a banker, born in Georgetown, at the time still a separate village from Washington. He prospered throughout his career, but became fabulously wealthy in the 1840s, when his bank financed the Mexican-American War. He was a philanthropist in many other areas besides his museum, and made large gifts to several universities.

Renwick Gallery, original home of the Corcoran collection,

17th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue

Corcoran Gallery, present location,

17th Street and New York Avenue

In the late 1840s, Corcoran bought a large house on Lafayette Square, which had been built by Thomas Swann, whose name appears as a buyer from James Breckinridge in the first document cited above. Swann (1765-1840) was a prominent Maryland lawyer; his son, also named Thomas Swann, later became governor of Maryland. After Swann’s death in 1840, the house was occupied for a time by Daniel Webster. Corcoran remodeled and enlarged it, creating an imposing Victorian mansion. Unfortunately, it was demolished in 1922 to make room for the U. S. Chamber of Commerce Building.

U. S. Chamber of Commerce Building

Finally (at least so far), document 1998.26.480 is a letter from Corcoran himself, dated March 13, 1851, once again pressing Cary Breckinridge to respond to his offers. Cary was apparently not a punctual correspondent. Here is the text of Corcoran’s letter:

Dear Sir, I enclose a press copy of a letter addressed to you on the 21 Feb to which I have had no reply. I would prefer taking the lots for the reasons stated; and keeping the matter open subjects me to inconvenience, having delayed the building of a stable on that a/c; but now that the Spring is opening, I would not like to delay it much longer. I have therefore to ask an answer by return mail, and if the price I offer is not satisfactory, state the lowest figure, & I will determine, at once, whether I will take them.

With that much information, I went to the District of Columbia Archives, where land records are kept, confident that I would find what I was looking for without much trouble. I was wrong; but the saga of my trouble at the archives will have to wait for another posting. After two visits, I nonetheless found the deed. It was signed on August 28, 1827, in Botetourt County, by James and Ann (Selden) Breckinridge, and recorded in the District of Columbia clerk’s office on December 8, 1827. The deed also yielded the indispensable first name of Mr. Smith, who kept the accounts. He was Clement Smith (1776-1838), a prominent banker, president of the Farmers and Mechanics Bank of Georgetown, and also a real estate developer. Several of his buildings survive in Georgetown, such as these Federal style townhouses on N Street, known as Smith Row.

Smith Row, N Street

The deed contains several parts. As was customary, Ann (Selden) Breckinridge was questioned apart from her husband, to ensure that she was signing of her own free will. She was interviewed by Francis Taliaferro Brooke (1763-1851), a judge of the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals from 1804 to 1851. The signings were witnessed in Botetourt County by Samuel Lewis Southard (1787-1842), a U.S. Senator from New Jersey, who had worked as a tutor for the Taliaferro family after his graduation from Princeton in 1804, and became acquainted with many Virginia political figures. In 1823 he was named Secretary of the Navy by President Monroe, and was briefly governor of New Jersey, before returning to the Senate in 1833. After watching the Breckinridges sign the deed, Southard swore before two justices of the peace in Washington, DC, on October 19, 1827, that the signatures were authentic.

James Breckinridge’s lots in Washington were in the heart of a very elite neighborhood. After her husband’s death, Dolley Madison moved back to Washington and lived on Lafayette Square. Benjamin Ogle Tayloe also had a house there; he was a son of John Tayloe, who built the Octagon House just a short walk to the west on New York Avenue; and he was a brother of George Plater Tayloe, who moved to Roanoke County and became a good friend of the Watts family. Although little is left of the original elegant residences, one can see online an artist’s reconstruction of the square as it looked in 1902, when many of the old buildings were still standing. There are even interactive buttons with information about the residents.

The Octagon House, built by John Tayloe

There is much more I’d like to know about James Breckinridge’s property. When did he acquire it, and from whom? Did he own land elsewhere in Washington? When did Cary Breckinridge finally sell the lots to W. W. Corcoran? Eventually, I intend to answer all those questions. When you read the story of my initiation into the District of Columbia Archives, however, you will understand why I don’t think I can finish the research before we go to London this summer. Elaine and I are leaving July 5 and returning August 11. The trip may disrupt or delay my blogging, but I will continue as best as I can. In the intervals, best wishes to everyone for a happy and productive summer.